23 for all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God, – Rom 3:23 NASB20

Sin is a Bad Word

“Sin” is such an ugly archaic off-putting word. I notice that a lot of popular theologians, apologists in the true sense, try to use more friendly words for it – “low anthropology”, or Francis Spufford’s pithy phrase “The Human Propensity to Fuck Things Up (HPtFtU).” I love these substitute phrases — I myself use “low anthropology” all the time. David Zahl wrote an entire wonderful book with this phrase as its title. I would use the HPtFtU more if I could remember the acronym. This post is not a criticism of using friendly substitutes for the word “sin”, far from it!

So, why use the old archaic term “sin” at all? I think we all know that each of us is “human” — as Jesus observes, we “look” with sexual interest, we say “you idiot,” we have some form of greed, we are not often good samaritans. Perhaps “sin” is too stringent a word for such normal aspects of humanity. But according to Martin Luther, the idea of sin reaches much much deeper into the human psyche:

“Our nature, by the corruption of the first sin, being so deeply curved in on itself (incurvatus in se), not only bends the best gifts of God toward itself and enjoys them… but it also fails to realize that it so wickedly, curvedly, and viciously seeks all things, even God, for its own sake.”

— Paraphrase of Luther’s commentary on Romans 7:7ff, from the Works of Martin Luther: Lectures on Romans

In other words, the idea is that we even do righteous good obedient things for very wrong and selfish reasons. Luther’s point is that we can’t eliminate the stain of this humanness from every little thought we think, every desire we have, every little thing we do.

The point of this post is: why is this a good way to think about ourselves? It seems deeply and even mean-spiritedly pessimistic! Surely we can do genuinely loving and altruistic things. Surely this does not describe the totality of human experience the way Luther is saying. We really do have to wrestle with the reasonable criticism that Christian theology goes overboard with this idea. EVERYONE has sinned? We have an “inward curve” so that even our best intentions are stained by selfishness and an intent to harm? Does this ring true?

At the heart of this question is an even bigger question: is the central Christian notion of salvation, of mercy and grace, of grand forgiveness, the right gift? It assumes not only a helplessness, but a terrible and inescapable evil that in some subtle way colors all that we are and all that we do. And that our approach to God is only defined by our inherent inescapable deep fault. Honestly, at first glance I wouldn’t want to approach any friendship or romantic relationship under this rubric. Are we all really such monsters? Is everyone truly covering over their own subtle or not-so-subtle selfishness and evil? Are we all to some degree narcissistic horrors? In our day-to-day lives, it just doesn’t always seem like it. There are wonderful people in my life that it seems ridiculous to define them this way. The idea of “salvation” seems to address a big giant nothingburger. Jesus died for my “sin?” What the hell is THAT? It doesn’t seem like an act of love. It seems like an accusation — and an overblown one at that.

So the Christian idea about people is that we should start with the absolute worst possible idea about everyone, and deal with them completely on this basis. Yes. To be clear, this is a view I wholeheartedly subscribe to, and I’ll explain why I think this is the most freeing and beautiful and genuine and loving way to view myself and those around me. I love this “doctrine” of sin, because I do think it describes the truth about us, and I want to explain why I think this is such a helpful and lovely perspective from which to view life on planet earth.

Sin is a Useful Word

So how can this be true? How can the idea of “sin” be beneficial and helpful? I am convinced that if you have a clearer picture of what all this talk about sin and salvation means, you will have a sense of freedom and a sense of being loved that is unsurpassed, and avenues to incredible closeness and authenticity in your relationships will open up that you could never have imagined. None of this is meant to frighten, condemn, or manipulate you into some fake “repentance” in order to conform to some kind of arbitrary archaic standard of religiosity. I consider myself an exvangelical, and I am not trying to use some kind of ham-fisted “evangelism” to trick you into joining my tribe.

First off, I want to celebrate the utility of the idea of “sin.” We tend to substitute other words like “brokenness” or “woundedness” for our troubles. Many times these really are the right words. But often such language is used to skirt the issue, to short circuit our guilt with a false absolution which pretends we were never at fault. I often have to quibble with my own therapist about this. He wants me to believe that I was not really at fault in a situation, that I should not feel guilt. Perhaps he is sometimes correct. But the fact is, I DO feel guilt about things, and I cannot simply flip a switch and turn off my sense of right and wrong. I need my guilt because I need a sense of justice and my self-flagellation is some kind of strange and inadequate comfort in that. The healing does not come because we sweep our guilt under the rug – it comes because we deeply confess the truth about ourselves and own the responsibility for our lives. I would rather receive absolution than pretend that I don’t need it when I do. Sometimes it is difficult to tell whether I really need absolution or not, so it is nice to live under the rubric of an overabundance of absolution and just be done with it all.

Secondly, and perhaps more importantly, I think almost everyone would agree that we labor under a sense of inadequacy, a lack of what David Zahl calls “enoughness.” We never feel that what we are and what we are doing is enough. On its surface, this means that we never feel that we have enough money, or that we are too obsessed with money. Or that we are not good enough parents – we are perhaps too neglectful or too controlling. Perhaps we feel that we are not altruistic enough, giving money and time to important causes and serving the poor and marginalized among us. Or perhaps we feel that we are too fat or too thin, or that we are simply overly concerned with our worth being tied to our body image. Perhaps our job or career or business path is unsatisfying in some way – it is insignificant or unlucrative or just silly. Perhaps we feel that our love life is a failure – it is shallow, tepid, toxic, or nonexistent. We are constantly beset with frustrations and doubts about ourselves and our place in the world.

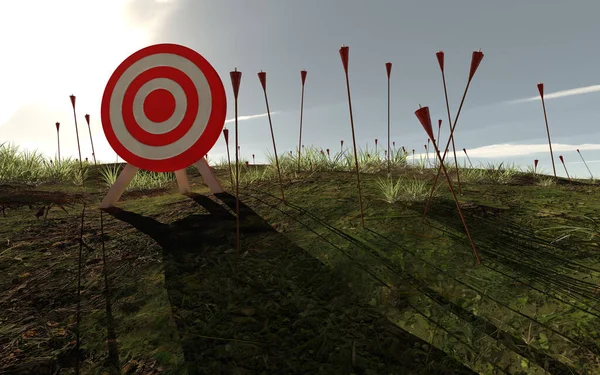

But the problem goes much deeper than all this. Our very souls live in a deep pit of doubt about our own significance. The Greek word in Romans 3:23 translated as “sin” is the the word “hamartia”. It means “a missing of the mark.” It suggests that you keep aiming at a target and missing. And this missing isn’t simply some transgression of a seemingly arbitrary religious rule. It is a falling short of “glory.” “Glory” is the Greek word “doxa” which is defined by words such as splendour, brightness, magnificence, excellence, preeminence, dignity, grace, majesty, exaltation. As Solomon says in Ecclesiastes 3:11, we apprehend the infinite but we are preoccupied with the finite. We are meant for splendor but we are caught up in the mundane. We are meant for dignity but we grasp for the shameful. We are meant for excellence but we settle for mediocrity. We have true love within our reach but we reject it out of fear or sheer laziness. We fall short of glory.

And so we seek significance because we feel the weight and responsibility of the insignificance of our only one and important life. It is our only life. Today is our only day that we can again grasp at glory and it is supremely disturbing that we fail. We are still poor. We are still too fat or too thin. We are still lazy and we still eat poorly. We are still addicted to destructive pleasures. We still love tepidly and fearfully. We want to be the Master of our fate and our souls, but we still carry a sense of our own failure and inadequacy and our not-enoughness. We are constantly thinking and working and dreaming and grasping for that glory, but it is never enough.

The people around us are never enough either. If I myself could be so tremendously glorious, it is all these people who surround me who stand in the way of my potential. They are using me for their own grasp at glory, at pleasure, at enoughness. I am a stepping stone for them and they are a stepping stone for me to achieve my glory. The world is so unjust!!! I cannot and should not love those around me because they have harmed me in real ways. I should never have been caught up in this job, this marriage, this family, these blocked opportunities! I should not have to endure this disease, this terrible loss! I could be glorious in the exactly perfect way that I perceive glory to be! Perfectly spiritual, perfectly at peace, perfect in prayer or contemplation or contentment. But alas, I am not, and this is not a trivial matter. It cannot be tossed aside as being “human.” The world I live in is deeply unfair and I cannot help but to continue to grasp for significance against all hope. It is the deep anguish of the existential angst of being human and being alive.

This is sin. This is the sin of my soul. It is the sin of the world. It is the very air we all breathe. We are caught in it like a fly on flypaper. Our very identity is that we lack glory and we must keep grasping for it, reaching for it, working and working and working to prove our significance in a world that refuses to see us. I am reminded of John Malcovich’s speech as the pope:

The girls who snubbed us, the boys who deserted us, the strangers who ignored us, the parents who misunderstood us, the employers who rejected us, the mentors who doubted us, the bullies who beat us, the siblings who mocked us, the friends who abandoned us, the conformists who excluded us, the kisses we were denied, because no one saw us: they were all too busy turning their gaze elsewhere while I was directing my gaze at you. Only at you. Because I am one of you.

Sorrow has no hierarchy. Suffering is not a sport. There is no final ranking. Tormented by acne and shyness, by stretch marks and discomfort, by baldness and insecurity, by anorexia and bulimia, by obesity and diversity, reviled for the color of our skin, our sexual orientation, our empty wallets, our physical impairments, our arguments with our elders, our inconsolable weeping, the abyss of our insignificance, the caverns of our loss, the emptiness inside us, the recurring, incurable thought of ending it all–nowhere to rest, nowhere to stand, nothing to belong to–nothing, nothing, nothing!

My deep deep friend Nathaniel Kidd worked with me to discover this truth. The nature of Christian of conversion is not about moral change. It is a change in essence. At our essence we are frantically working to overcome our insignificance, our lack of glory. But the change is a change of essence, a fundamental change of belief. We come to believe, not that we are judged, but that we are loved. We are loved defacto, without change. We come to believe this:

16 We have come to know and have believed the love which God has for us. – 1Jo 4:16 NASB20

The infinite One, the One who IS LOVE, considers us His pearl of great price — worth throwing away every other thing to obtain. We are tremendously loved. We are infinitely and eternally significant because the infinite eternal One has loved us with an impossible sacrificial love. We can lay down our frenetic grasp for glory and significance because we are glorious and significant NOW. Our essence changes from grasping for a love which is never there, to basking in a love which will never end.

And the reason all this talk about sin and redemption and forgiveness and justification is so important is that our souls will never stop creating doubts about whether or not that is true or deserved. The very idea of deserving has been destroyed. It is always so easy to consider ourselves undeserving and inglorious. We will always need the assurance that we have been gifted enoughness. As believers in a God of love, every possible sin, every possible shortcoming, even the worst possible moral failure, all impediments to belovedness have been destroyed. Our own doubts about ourselves cannot vanquish the power of the great love of God for us. Even if we were to kill God’s only Son, it is proven by the resurrection that it cannot discredit God’s love towards us. All is forgiven because we are the objects of intense real unstoppable love. This is the true nature of forgiveness. It turns out the ultimate sin is to believe you are not loved, that you must deserve it and earn it. Faith receives such love as a gift, and says yes. It is truly finished.